It was the last day of school and very hot, so Mlle. Lisette Leccese held the lessons outside, in the light breeze and the shade of the great storm-oak. The two largest boys had moved the board outside for her, and she was improving the day with a last round of geography. Most of the children were soon off somewhere for the summer, so it seemed a good choice.

After she had sketched the English and French coasts on the board, she added some dots and asked, "What is this big one here, in England?"

"London!" shouted several voiced. A wit in the back mewed and was joined by others. Take that, Whittingtons.

She sighed. "And this dot on the coast?"

"Dover," said fewer voices.

"And across the Sleeve in France?"

"Calais."

"We're going there," piped Jeanette, "to see my aunt."

"Where is our town?" asked Hubert. He was only five and barely understood maps.

"England and France are in la zone basale," Lisette explained patiently. "Mer-sur-Ys must go on another board, for Brequelle."

But Hubert's attention had wandered. Now she noticed several other children were also looking down the road. It was a plain dirt road, and something was kicking up a great deal of dust. Next, she heard the clop of hooves and saw figures on horseback. Interesting! She and the children watched expectantly.

A few moments later, she cocked her head in puzzlement, as did some of the children. The hoofbeats, she realized, came in a solid rhythm. And something about the figures... Then came the singing—men's voices, singing English:

O'er the hills we'll march today,

The King has called so we obey.

We'll stand our ground and here we'll stay.

Over the hills and far away!

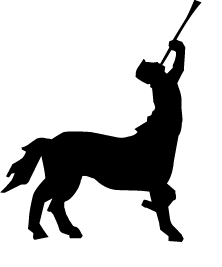

The voices were not exactly men's. Not fay. Certainly not merfolk. Not deeper than men's voices, but more ringing, more resonant. And now they were nearer and she saw they were not riding horses after all. Of course they would have more resonance, with two chests each.

"What are they?" Robert asked. One of the older children told him and Lisette wrote it on the board so all could see how it was spelled.

To the shores of endless night,

We will march to stand and fight.

Mortal, fay, we're brothers all,

Remember us if there we fall...

There were no wars nearby. They could not be heading into battle soon, but of course they were soldiers, cavalry: that's what they sang about.

The song ended a few score yards away. "Fall out!" called a single voice. "At a walk!" They fell out of march and slowed, still approaching.

Lisette watched, fascinated. She had seen photos, of course, even short video clips on the kingdom's Nor'Net feeds, but this was the first time she had seen one in person. And not one, but half a dozen. No, eight, ten. No, the last two were actual horses.

They were an intimidating sight. And here she was, at the edge of town, with children in her charge, confronted with these creatures, soldiers and war-horses combined. Well, all she could do would be to yell "Run!" and lead the children into the woods, not that that would help much. Meantime, it seemed sensible to treat the event as a surprise parade, as the children were doing. These were the king's own troops, after all.

As the dust settled, one approached, closely followed by a second. He wore a tan military jacket and a wide-brimmed hat. He carried a pack on his back—his human back—and four more behind his equine shoulders. His face was quite human, white-bearded, red with heat, with bright blue eyes. His equine body was a dun—light tan with dark brown legs and tail—and a few traces of brown lingered in his beard.

When he set foot in the school yard, the voice of the schoolhouse brownie shrilled, "Return, and we return!" He looked toward the sound, coming from somewhere in the schoolhouse thatch, and doffed his hat, answering, "Keep faith, and so do we." His troops followed his gaze and raised their hats.

The leader then doffed his hat again, this time to Lisette, and bowed, stretching out one foreleg as she had seen performing horses do. "Good day, mademoiselle. We apologize for interrupting your class." His was the voice that had called the orders. His Chenelaise leaned toward the English side; they must come from that base in Berkshire. What was it called?

A beat after his bow, his attendant—his lieutenant, she saw from the insignia—also uncovered and bowed. He was a tall palomino with blond hair and beard, long waxed mustaches drooping in the heat.

Behind the two of them and another beat later, the rest of the company raised hats and bowed. If they had not been a little out of synchronization, it would have been comic or eerie. Six young men—well, they were compounded of young men—all bearded, all in the same gear as their captain and laden like him: A great black draft standing next to a much slighter chestnut. A palomino fanning his beautiful face with his hat and gazing wistfully at the children. A paint with a foxy smile. A big bay and a slightly smaller buckskin standing quiet and sober. At the back stood the two actual horses, a bay and a gray, bearing packs and wearing hats like the soldiers. The young chestnut held their leads.

It pleased her that she remembered the names for the coat patterns. She had seen too little of anything equine, for too long. She had not even ridden since last summer.

While she took all this in, the elder had completed his bow and was saying something about not wanting to impose.

"Ce n'est rien, captain," she replied, happy at spotting his rank. "It is the last day of school and you have provided the children with something much more educational than an outdoor geography lesson."

"You're very kind. With your permission, might my lads use your well?" He nodded toward it.

"Certainement! The water is quite good. Gerald, Andrea, assist the gentlemen."

"That's unnecessary, mademoiselle," the captain began, but it was clear that it would take industrial machinery to get Gerald and Andrea away from that well. The other children flocked after.

The soldiers unbound some of the packs from themselves and the horses, then approached, making the school yard much more crowded. While the children raised and lowered the bucket and passed around the iron cups, the captain made introductions: "Captain Philip Fletcher of the Royal Dedicated Cavalry, in your debt, mademoiselle. And this is my lieutenant, Liam Sanders."

"Lisette Leccese. Are you taking ship?" She nodded down the road, not meaning Mer-sur-Ys, which had only fishing boats and other light craft, but Côte d'Ys further down the coast, silhouetted against the rainbow mists of the sea-march at the Edge.

"C'est vrai. My lads must get their sea-legs. Which of course is twice as hard for us!" She laughed in return to his grin, but the remark was also useful. It told her, "We don't mind talking about what we look like, what we are."

He went on to tell her that, in Côte d'Ys, they would join with units of the infantry and "standard cavalry" to take the sea passage to Yesod-Khonsu, where their journey would really begin. The "lads" were first-timers, trainees. He had led such groups many times before, but not recently past Mer-sur-Ys.

She told him she had been teacher here for only four years, and wondered if her predecessor had ever met the captain.

She saw that, behind Fletcher's back, the bay had nudged the buckskin with his hip—this would have staggered a man but merely attracted the buckskin's notice—handed him a couple of iron mugs, and nodded at the two officers. The buckskin paced over and handed the cups silently to his superiors, who thanked him. Lisette thought it probably spoke well of Captain Fletcher that he had his men drink first and that they then spontaneously waited on him.

Meanwhile, Lisette took tally of her own subordinates. "Hubert! Jeanette! Stop bothering that poor fellow!" The huge black draft was standing statue-still, a nervous smile on his face, while the two children raced in and around his legs. Only his head moved as he tried to track his invaders. The children barely had to duck as they ran under him.

Perhaps in obedience to her command, Hubert and Jeanette raced away to some other devilment. The draft relaxed. He smiled at Lisette and saluted. "Poor fellow," she said to the captain. "He must feel he walks through a world of tissue paper."

Fletcher had watched the interaction with a smile. "He enjoys every moment of it. The transformation was very kind to him. A few months ago, he was thin as a rail and dying, gasping for every breath."

"I am surprised the deathly ill do not flock to the Dedicated Cavalry in hordes."

"Usually, it would not help. The healers could do nothing for him themselves but scried that he was a rare case that transformation would cure. Such unfortunates more often join the fays, if they can."

"So you're not fays?" asked Susanne, the eldest girl. She had been standing silently at Lisette's side, watching. "You're not magical?"

"We are mortal," Fletcher affirmed. "We were made from men. Each of us used to be a little boy like this one." He nodded down to where Hubert had paused in his latest orbit to stare at the captain. He stayed, apparently mesmerized by the equation Fletcher had just made. "When we grew up, we went to the Dedicated Cavalry and asked to join, and so be transformed. We were changed by magic, but we have no more magic than we went in with. Are you answered?"

"Yes, thank you," said Susanne. "Do you take girls?"

"The spell was copied from some magic arrows we found. It only works on males. We haven't found one that works on females."

"Oh. Arrows?"

"We are changed by being shot."

"Oh! Does it hurt?"

Fletcher shook his head. "It is very confusing, but it doesn't hurt."

Lisette surveyed the soldiers. "I have wondered how people come to choose transformation. Do you know the story for each of your men?"

"Yes, some are simple, some not. Some of the lads are open about their reasons, others private. Myself, I'm simple and open: I follow the hoofprints of an uncle I loved, who enjoyed this life greatly."

She continued gazing, trying to guess what each soldier had looked like as a man. If the draft had changed so much, how could one guess? And what would they be like, what would they each be doing, if they had not chosen this change? Dying or rotting, in one case, of course. Their very bodies were a puzzle: hips were shoulders, necks were waists. Beautiful horses. Strong young men. Comely monsters. Unnatural but harmonious.

"Yes, transformations baffle that way," said Fletcher, apparently reading her gaze. "What is, what was, what could be or could have been, all swirled around. Like any birth or death or maturation, but faster and stranger."

"You are a philosopher, Captain."

"Scholars on hooves, mademoiselle, that's us."

"Can I have a ride?" It was Jeanette, suddenly at the captain's forefeet, staring up at what must have looked like a grandfather to her, and grandfathers were easy. And a grandfather who was a pony at the same time? Not to be missed.

"Jeanette!" she remonstrated. "The poor fellows are tired–"

"Yes! You may have a ride!" the captain interrupted. He scooped Jeanette up and dropped her down on his lieutenant's back. The lieutenant reciprocated by seizing Hubert, who was of course under foot, and depositing him on his captain's back. Behind them, the soldiers grinned and chuckled. She caught the phrase "like he said." It seemed this was some inside joke.

"This march is an endurance exercise, mademoiselle," the captain told her. "We were hot and thirsty—no longer, thank you—but we have no business being tired."

All the soldiers were kneeling now, and small children were scrambling onto their backs in twos and threes. She heard repeated instructions to hold onto the straps on the backpacks. Then they all paced clockwise around the schoolhouse, a living merry-go-round.

Only once around, then everyone off. Wise restraint. Then the big draft invited the older children on. Giggling and gingerly, they accepted as he and all the others, including the captain and lieutenant, knelt again. Hubert marched behind the big draft, lifting his knees exaggeratedly, clearly pretending to be one of these magnificent soldier-horses. She worried, for a moment, that he might get kicked by accident, but the draft moved to the side a little, then fell back, and soon had Hubert marching beside him rather than behind.

Jeanne was riding the paint with the sideways smile. Jeanne was next oldest after Susanne and physically ahead. A tiny worry skittered through Lisette's mind again: What if he simply took off with her? The answer came immediately: His fellows would run him down and trample him to paste. Anyway, the paint bore an expression of wry patience, no more.

Fletcher came round, unloaded two boys, then gestured down his flank and said, "Mademoiselle? The carousel is still open."

"Oh!" She felt herself blush. "I'm not dressed for–"

"There is a decent horn on the saddle. You could hook one knee over it and ride side-saddle. Have you done that before?"

"Bien sûr." And she climbed on. It was the easiest mounting of a horse—an equine—she had ever done, since he knelt for her. When was the last time she had had a chance to ride a horse? Much less a ride like this. She was of one mind with Jeanette: not to be missed.

Considered as a ride, it had its drawbacks. Fletcher apologized for having no stirrups. The saddles, she learned, were there for his lads to practice with; no one had expected actual riders. Fletcher had taken off a couple of packs, but two remained and got in the way. And, decent horn or not, a standard saddle is not a side-saddle. But he made it almost embarrassingly easy, pacing smoothly around with the children following, cheering and chattering. He smelled of a mixture of man-sweat and horse-sweat, but not badly, and it reminded her of the last ride with Jules, last summer, too long ago.

This was sure to get back to Jules. But that was a good thing, she decided. It could start an interesting conversation.

"Rank hath its privileges," the captain murmured under the noise of the children. "If anyone gets to carry the one grown woman here, it's going to be me." She laughed and felt the blush again. This was the second or third time he had echoed her thoughts, and she wondered if he were Receptant.

"Don't say the name," he continued.

"What name?"

"Nessus."

"I wasn't even thinking it."

She felt a single kick of laughter run through the ribcage under her. "Mademoiselle! To not say it is discreet. To not think it is insulting!"

She laughed again. "If it helps, I was thinking something of the sort when your fellows were giving rides to the older girls."

"Yes, we have a reputation to repair, even after three thousand years."

"You are doing very nicely." And she considered that Fletcher was also taking care of her reputation. If she had ridden that golden horse-god, for instance, the conversation with Jules might become too interesting.

Once around the schoolhouse, then he knelt and she dismounted, thanking him. She made him and his troops take another round of water and refill their canteens. She inquired after the actual horses and learned the young chestnut had watered them already. She and the children helped them strap packs back on. Then they bade them goodbye with genuine regret and watched them march away.

O'er the hills we'll march today,

The King has called so we obey.

We'll stand our ground and here we'll stay.

Over the hills and far away!

Hubert marched in place as he watched, clearly entranced. Lisette considered his white-blond hair. Perhaps he would make a handsome palomino someday.

Return to Cavalry Cycle

Return to Inkliverse

Return to Wind Off the Hilltop

Copyright © Earl Wajenberg, 2017